The global trade war took another recently, with no last-minute reprieves, extensions, or “chickening out” from the Trump Administration. New Zealand has been dealt a reciprocal tariff of 15%, revised up from 10%.

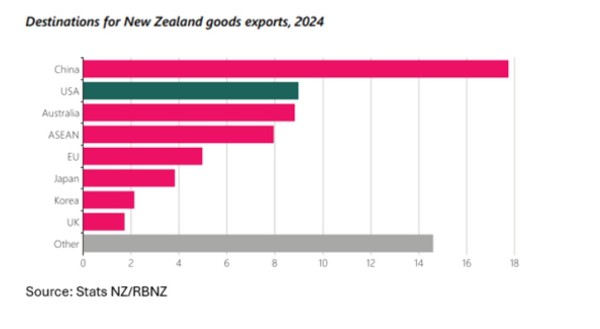

We have fared better than some countries (Switzerland copped 39%), but there has been a degree of shock from some quarters, including over the treatment we have received from our second-largest trading partner when compared with that meted out to our export competitors such as Australia, which has been let off with a 10% rate.

The suggested reasons have ranged from NZ running a trade surplus with the US (albeit a small one), and our GST rate of 15%. It also has been suggested that our political ties with the US aren’t as strong as some others (the FBI opening an office in Wellington may have been too little too late), while we also have a nuclear-free policy. Ultimately, not having a bilateral free trade agreement (while Australia does) may also be a factor.

The epilogue to the announcement is now likely to see some lobbying by our officials (and those of other countries) to get a better deal. This will, though, as we have seen with other agreed deals, have to include something on the other side, as there are no free lunches in Trump’s trade offensive.

So what happens if NZ is stuck with 15%?

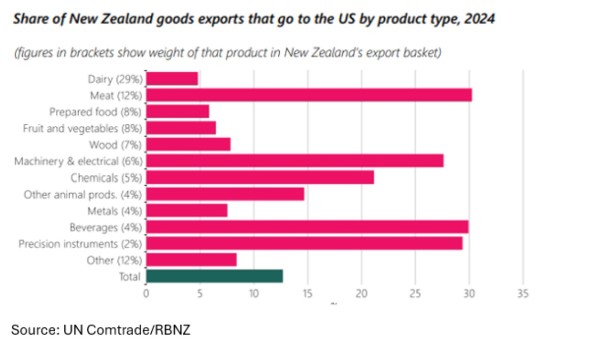

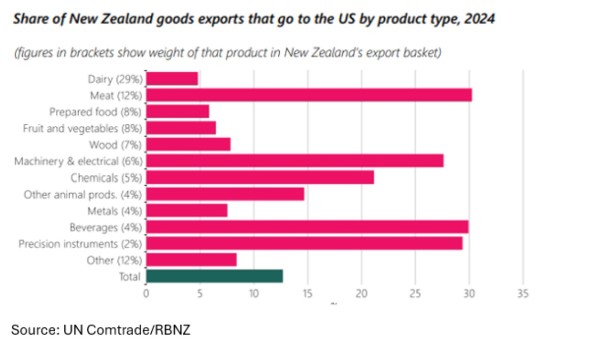

Prior to the recent announcement out of the White House, we were all seemingly comfortable with our lot – a 10% tariff. We export around $9 billion of goods to the US, and duties of around $900 million would be material, but manageable. We are now faced with duties of $1.4b. Some commentators have suggested that this is still “digestible” in the context of our $400b economy, but the reality is the tariffs will affect an important segment of exporters which have been among our brightest stars recently.

With much of the NZ economy stagnant, our agricultural exporters have been flourishing, and not least of which has been the dairy sector amid strong global demand. Fonterra has acknowledged that tariffs will impact sales of dairy ingredients and products in the US, a market that accounts for 10-20% of Fonterra’s sales.

We sell $1 billion a year of dairy product to the US, and that is too much to divert elsewhere. The question then becomes whether Americans will be prepared to pay more for our dairy products, or will the industry have to eat the tariffs? A saving grace is that many of our global export competitors are based in Europe, which is faced with a similar tariff rate.

The playing field is not so level for our red meat industry, for which the US is our largest market, with exports of over $2b. Our farmers have benefited from shrinking US herd inventory, strong demand and high prices. Beef & Lamb NZ estimates that tariffs will cost the industry an extra $300m a year.

And while competitors in Brazil (at 50%) are facing much higher tariffs than our meat farmers, those in Australia, Argentina, and Uruguay are only having to deal with duties of 10%. This could well put Kiwi meat farmers (which have been used to minimal tariffs), including the likes of Silver Fern Farms and Alliance Group, at a clear competitive disadvantage, with knock-on impacts to margins and/or demand (already down 14% since April).

Then there is the wine industry, set to be facing over $100m worth of extra tariffs. The US is our biggest market, with annual wine exports of around $750m. Price points for American consumers have been very sensitive, and $1 or so of duties on a bottle of sav (90% of export volumes) could make all the difference between consumers choosing our wines or something cheaper – either homegrown or from the likes of Australia, Chile or Argentina, for instance, which are dealing with lower tariff rates.

A host of other industries are facing similar headwinds, including primary sector machinery (+$600m per year in sales) and seafood (+$300m per year), along with pharmaceuticals.

On that note, our largest listed company, Fisher & Paykel, derives around a quarter of its global revenue from the US and does not have a lot of pricing power with its products. However, it appears that the company is relatively insulated in that the majority of its US sales are supplied from Mexico, which is exempt under the USMCA agreement. That said, this agreement is up for review in 2026.

All in all, there are a host of implications from the tariff announcement, and none should be treated lightly. Many of our industries that have been outperforming, particularly dairy and meat, will now be faced with competitive headwinds. They will have to decide whether to try to divert their products elsewhere or possibly absorb the effect on their margins, with consequent potential impacts to profitability, employment and investment intentions.

This will have knock-on effects on our broader economy. The headwinds will trickle down to affect underlying economic growth, investment, confidence, and employment when we least need it.

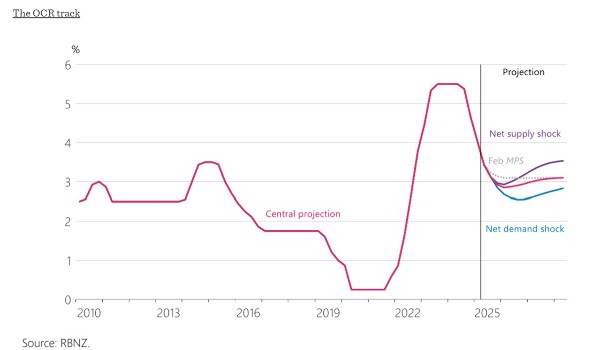

The Reserve Bank (RBNZ) was already predicting that increased global tariffs were likely to slow global economic growth, and we now have a direct hit on our economy, just as it’s crawling out of recession. Estimates were for our economy to grow around 2% next year. That is now looking like a tougher ask. There is the added complication that China, our biggest customer, while having had its trade “truce” extended for another 90 days, has yet to ink a trade deal with the US.

There are some positive takeaways, though, and it could be worse. Even in the light of the tariff announcement, we still have an open economy with free trade with three-quarters of the world, covering products that are regarded as very high quality and are in strong demand. Some traditionally US exports may be diverted elsewhere.

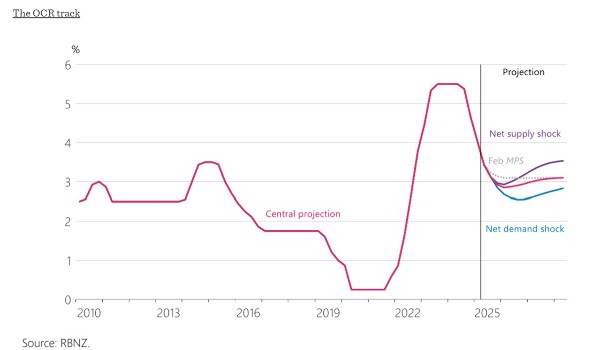

There will be a clear economic impact, but one that should compel our own central bank to cut rates when officials meet this week. There has been some added pressure here with the Reserve Bank of Australia cutting rates by 0.25% at their latest meet. Australia has cut rates and our economy is arguably in far worse shape than theirs – they are at least growing. NZ’s economy (agriculture and tourism aside) has been tepid and unemployment is rising - our jobless rate is 5.2% (6% in Auckland!) vs 4.3% in Australia.

Even though the RBNZ focuses on price stability it has an awareness of where the economy sits. Australia’s inflation rate is 2.1%, and we are at 2.7% but this is still within the RBNZ’s 1-3% range. The pressure is on for at least a 25-basis point rate cut by the RBNZ.

A RBNZ rate cut would provide support for positivity for domestic borrowers, local businesses and consumers. This is against a backdrop where our inflation rate has already fallen, and the scope exists for Trump’s tariffs to put additional pressure on prices in NZ as products destined for the US are shipped here at lower prices.

From an equity market perspective, our biggest company stands fairly insulated against tariffs, as do many of our other big blue chips.

Overall, global equity market confidence has also remained strong, despite the macroeconomic uncertainties of recent months, some of which have been resolved (the US has agreed trade deals with Britain, Japan, Europe, and several Asian countries, including South Korea). The equity markets have had a lot thrown at them in the past months, but have been resilient – the world’s biggest stock market, the S&P500, is trading around record highs.

Ultimately, stock markets are forward-looking and are sending positive messages, as are corporates with the earnings season in the US and Europe under way. For a world that has seen plenty of crises in recent years, are we just possibly looking at another shock that will play out better than feared?

Search

Search